When I began offering a selection of my comics-related writing a month ago, the impetus was the near-simultaneous release of the documentary Art Spiegelman: Disaster Is My Muse and the Dan Nadel biography Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life. I finally address Robert Crumb in this post, but first a short update on the Spiegelman film.

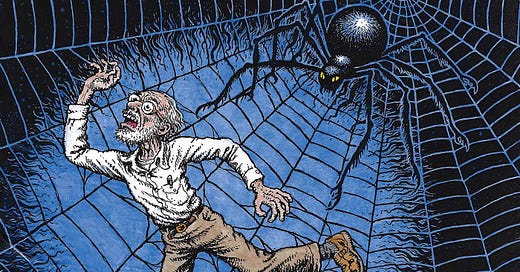

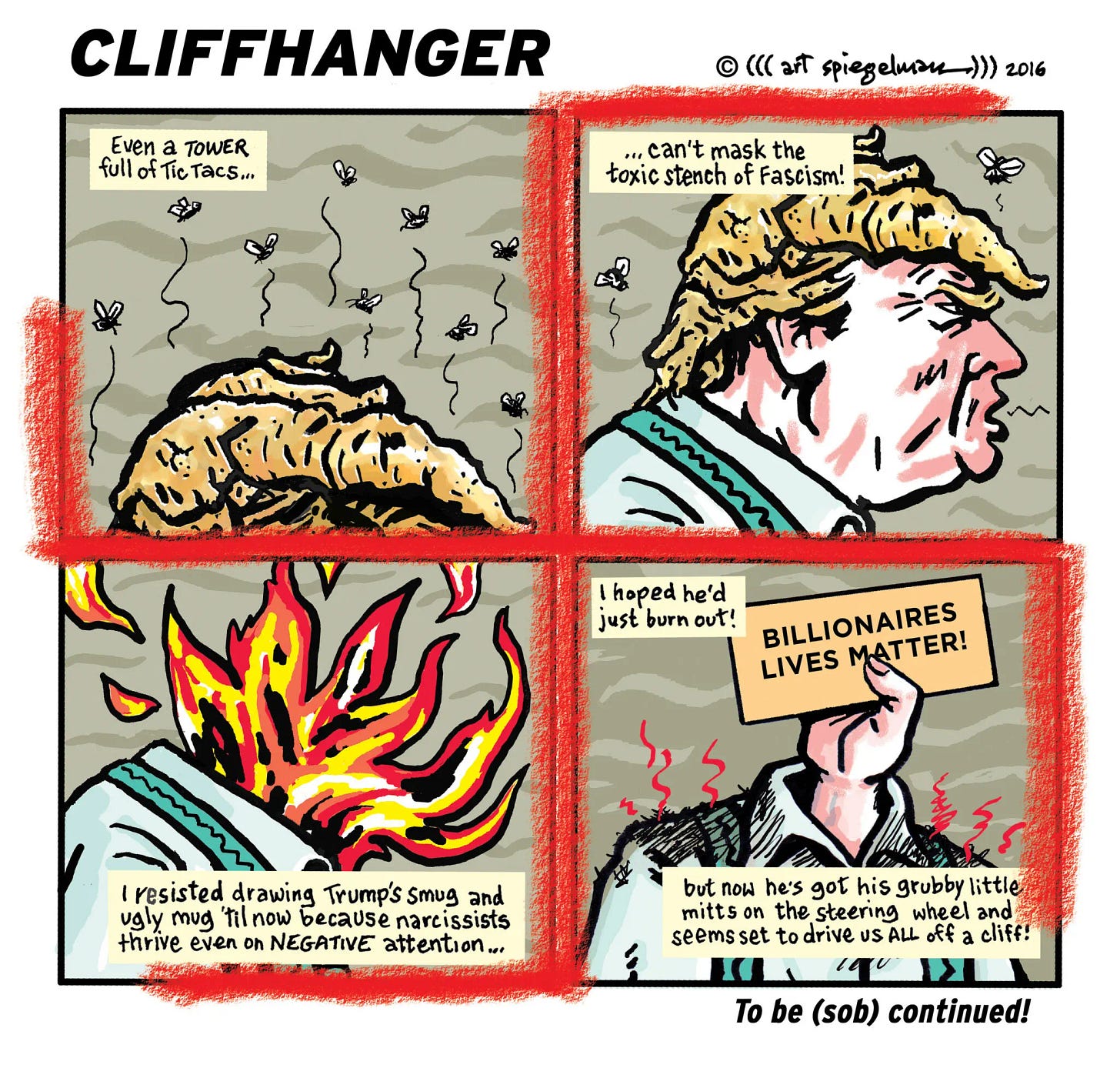

Before writing my review, I was unaware that PBS’s American Masters, where the documentary aired, had deleted approximately 90 seconds from the original cut, which premiered in uncensored form at DOC NYC. The segment showed and discussed a Spiegelman anti-Trump cartoon that he drew for Resist!, a publication co-edited by his wife, Françoise Mouly, and daughter, Nadja Spiegelman, in conjunction with January 2017’s Women’s March. The International Documentary Association’s Documentary magazine broke the story on May 19 in a piece that outlined not just this act of repression but other instances in which PBS – in what will inevitably prove a vain attempt to avoid Trumpian rage – has cravenly chosen to anticipate administration upset by removing potentially offending content. You can find a portion of the excised sequence at this Instagram post, and here’s the actual cartoon:

In a New York Times article on May 23, an official from WNET, the producer of American Masters, offered this transparently ass-covering rationalization:

Stephen Segaller, the vice president of programming for WNET, confirmed in an interview that the station had informed the filmmakers that it needed to make the change. Segaller said WNET felt the scatological imagery in the comic, which Spiegelman drew shortly after the 2016 election — it portrays what appears to be fly-infested feces on Trump’s head — was a “breach of taste” that might prove unpalatable to some of the hundreds of stations that air the series.

Uh, right. Given that the documentary decries efforts to ban Spiegelman’s Maus from schools and libraries, what most viewers will find “unpalatable” is the cowardice PBS exhibited with this self-censorship.

The Times also quoted Spiegelman’s reaction: “It’s tragic and appalling that PBS and WNET are willing to become collaborators with the sinister forces trying to muzzle free speech.” In an excellent Atlantic article on the imbroglio – recommended for those with access to the paywalled publication – Spiegelman uses more colorfully descriptive language for PBS’s actions: “This seems like volunteering to pull the trigger on the firing-squad gun.”

Now, to Robert Crumb – or, as he prefers to credit himself, R. Crumb.

I no longer recall exactly when I first encountered Crumb, but I suspect that I became aware of him through Ralph Bakshi’s animated adaptation of the cartoonist’s Fritz the Cat (1972). I was frustratingly denied access to the film itself for several years because its X rating prevented admission to anyone younger than 18 (I was a tender 15 when it arrived in St. Louis at the Fine Arts Theater in May 1972). That didn’t stop me from reading about the movie, however, and as an animated-cartoon obsessive, I devoured Michael Barrier’s deeply reported two-part examination of Fritz’s making in his sophisticated fanzine Funnyworld (issues No. 14 and 15, to be precise). In the articles, Barrier reproduced a tiny sampling of Crumb’s art – just enough to intrigue me – and I was then truly gobsmacked (and, in all honesty, thoroughly scandalized) when I encountered far more of his work, in all its unexpurgated excess, in Mark James Estren’s A History of Underground Comics in early 1974.

The first actual Crumb comic I owned was a copy of Despair, which was delivered into my hands – I’m guessing in fall ’74 – by my father, who presumably acted as an unknowing mule. As I dimly recall, someone at his workplace, then called Lewis-Howe (the makers of Tums), had a small stash of unwanted comics to offload. Because I had worked at Lewis-Howe during three summers in the early ’70s, it’s likely that the co-worker remembered that I was a comics nerd and suggested that my dad pass the books on to me. Although mostly an uninteresting hodgepodge of mainstream titles, which I no longer found of much interest, the stack also contained several undergrounds – I recall Ted Richards’ Dopin’ Dan No. 2 among them – and the Crumb comic immediately revealed itself as the gold nugget glittering seductively amid the dross. Those other books have long since disappeared, but that well-worn, yellowing copy of Despair remains in my possession more than 50 years later.

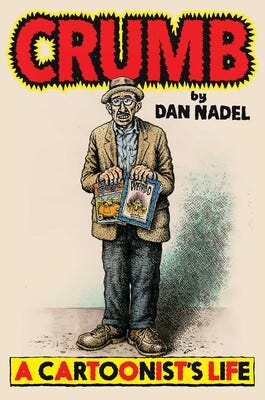

In the time since, I’ve accumulated enough Crumb-related volumes to fill an entire bookshelf, so I was particularly excited by the announcement of Dan Nadel’s biography of the artist. An art scholar and the curator-at-large of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art – slated to open in 2026 – Nadel has a sterling comics background: To cite only a fraction of his credits, Nadel was an editor of The Comics Journal from 2011-17, co-founder of the zine Comics Comics and the journal The Ganzfeld (which featured significant comics content), and editor of the books Art Out of Time: Unknown Comics Visionaries, 1900-1969 and Art in Time: Unknown Comic Book Adventures, 1940-1980.

Nadel’s book met my lofty expectations, providing not just a thorough overview of Crumb’s life but also keen critical insight into his art. Although obviously a serious admirer of Crumb’s work, Nadel doesn’t hesitate to plumb the Stygian dark recesses of the cartoonist’s personal relationships and artistic creations. Crumb, though written with its subject’s participation, resolutely avoids the sanitized, flattering portrayal of an “authorized” biography – an approach fully in keeping with Crumb’s own uncensored approach to his comics. To quote Nadel’s foreword:

Robert imposed just one condition on this book: that I be honest about his faults, look closely at his compulsions, and examine the racially and sexually charged aspects of his work. He would rather risk honesty and see if anyone could understand than cooperate with a hagiography. After I promised all of that, Robert agreed to this project with a shrug: “I’m not opposed to it.”

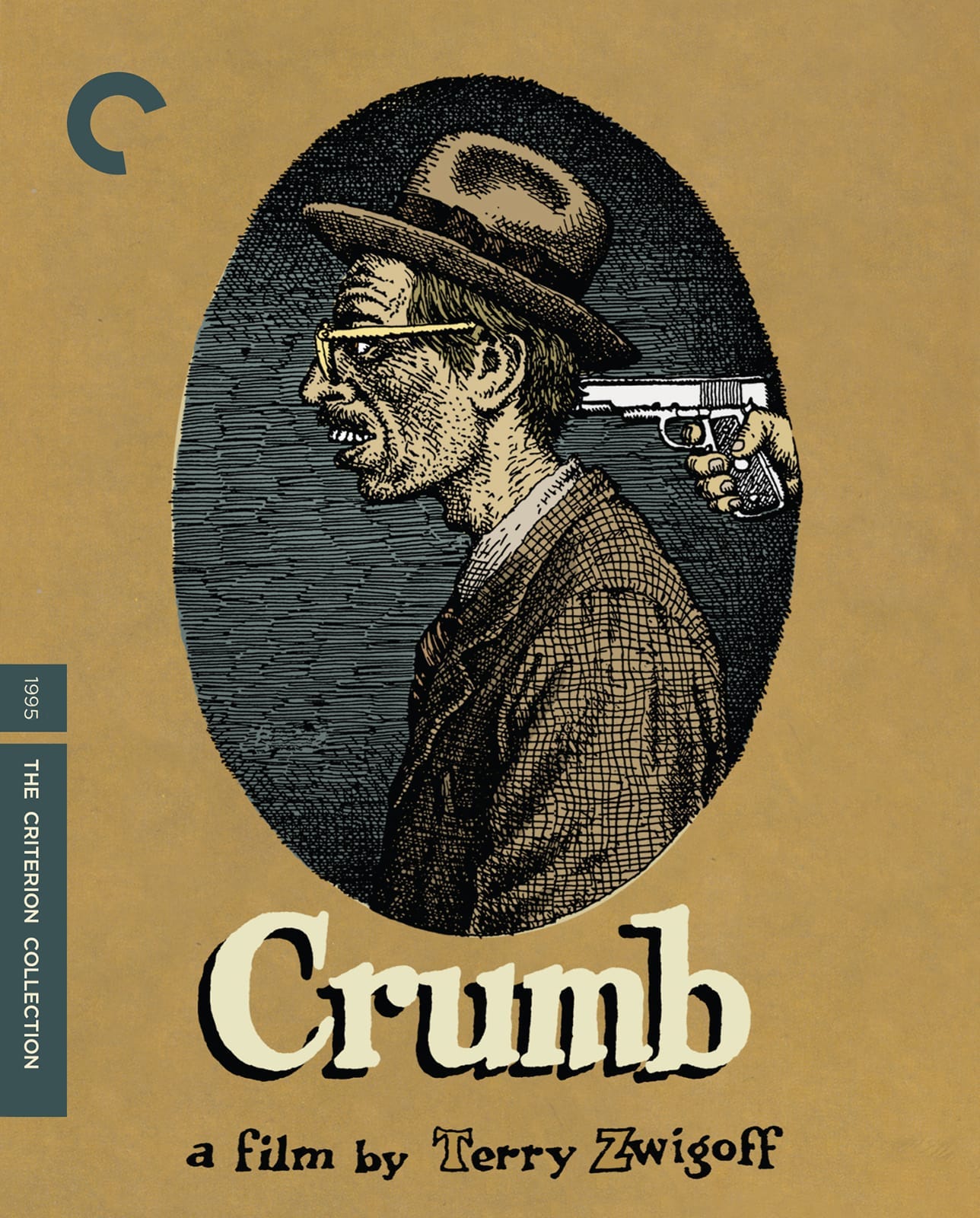

Viewers of Terry Zwigoff’s superb documentary Crumb already know the important basics of the cartoonist’s life and career, but Nadel fills in that outline with the sort of hyper-detailed crosshatching that’s characteristic of Crumb’s art. The book first explores Crumb’s dysfunctional family life – including the crucial controlling influence of his older brother, Charles, who insisted that Robert co-create their homemade comics with clockwork regularity – before chronicling his 1962 escape from his repressive Philadelphia home at age 19. Moving to the Cleveland apartment of his friend Marty Pahls, Crumb landed work and quickly ascended at American Greetings card company, produced a significant early solo work (eventually published as The Yum Yum Book), and married Dana Morgan (his first girlfriend after a miserable high-school experience as a dateless incel).

Robert began his journey to cartooning superstardom when, after sojourns in New York and Europe, he took an entirely different kind of trip by dropping acid for the first time in June 1965. LSD helped Crumb tap into a wellspring of creativity, and the work that came to define the artist soon started to flow, trickling first into his sketchbooks before eventually building into a raging torrent. As Nadel writes: “For Robert, there is life before LSD and life after. Nothing was ever the same.” At this pivotal juncture, as Crumb was gaining confidence both professionally (publishing pieces in Mad creator Harvey Kurtzman’s Help! magazine) and personally (engaging in several affairs), he moved to New York City, where he found inspiration in a nascent underground-comics movement in the East Village Other (EVO) newspaper. While working at Topps, the trading-card company, Crumb told boss Woody Gelman of his eventual plans: “Bob Crumb spoke to me of this desire to do an underground – he didn’t call it that, he just said he wanted to do dirty comics.”

His ambitions took awhile to realize – the peripatetic Crumb first spent time in Chicago and back in Cleveland – but in 1967 he landed in San Francisco, with its burgeoning counterculture scene, and those “dirty comics” began to surface in the adult magazine Cavalier and such underground papers as Yarrowstalks and EVO. Finally, in February 1968, Crumb published Zap No. 1, essentially instigating a comic-book revolution by aiming his work squarely at a mature audience – as the book playfully warned, these comics were intended “for adult intellectuals only!” In relatively short order, other artists produced their own underground comix – the “x” helping to distinguish the books from comics for kids – but Crumb was recognized as the undisputed standard-bearer, a preternaturally gifted artist who appeared to tap directly into the era’s zeitgeist. Despite the gathering acclaim – he was already being courted by mainstream publishers such as Viking (for the paperback collection Head Comix) and soon contributed the cover to Janis Joplin and the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills – Crumb was far from a possessive egotist. He generously opened subsequent issues of Zap to additional artists, for example, and it evolved into an all-star book, with such underground luminaries as Victor Moscoso, Rick Griffin, S. Clay Wilson, Gilbert Shelton, Spain Rodriguez, and Robert Williams becoming regular contributors. Crumb proved extraordinarily prolific in the years that followed Zap’s debut, producing a seemingly endless stream of solo books in a six-year period: Motor City, Big Ass, Despair, Uneeda, Mr. Natural, Homegrown, Hytone, XYZ, The People's Comics, Artistic Comics, Black and White. And because Crumb’s presence boosted the popularity of any comic in which his work appeared, he also supported undergrounds generally by contributing strips and covers to a confounding number of anthology titles.

Crumb’s productivity is all the more remarkable given the tumult of his life at the time. His marriage to Dana, after the red-hot ardor of their first years together cooled, was chronically troubled, and Crumb often lit out for new (or old) territory and indulged in both frequent dalliances and long-term relationships (one of the most serious was with ’70s girlfriend Kathy Goodell, who appears in the film Crumb). Further complicating matters was the birth of their son, Jesse, in April 1968 – a responsibility that Crumb was unwilling to shoulder properly. (The two had an on-again, off-again – and always difficult – relationship until Jesse’s death in 2017.) Despite their problems, Robert and Dana somehow stayed together, and in late 1969 the couple moved to rural Potter Valley in Northern California, where they lived in quasi-communal fashion. Both Crumbs had other sexual partners, though Dana sometimes exhibited a proprietary attitude toward Robert, and in 1971 the woman who would become Crumb’s second wife, fellow cartoonist Aline Kominsky, entered his life. In 1972, Aline moved to the Potter Valley property, where she, Robert, Dana, her lover Ed Sanders (of the Fugs), and Jesse uneasily cohabited (albeit in separate quarters) until the final dissolution of the marriage in 1974. Decamping to California’s Central Valley, Robert and Aline eventually settled in Winters, and the chaos of Crumb’s life slowly began to subside, though the IRS’s pursuit of back taxes created a fraught financial situation that didn’t resolve until 1978, the same year the couple married (at the unromantic suggestion of their accountant). The iconoclastic Crumbs – well matched in their artistic pursuits and sexual proclivities – maintained an open marriage throughout their more than 50 years together, but in 1981 they made a small gesture toward conventional family life by welcoming a daughter, Sophie, with Robert happily assuming a far more active parenting role than with Jesse.

The alignment with Aline yielded additional benefits: Although his taboo-breaking comics of the late ’60s and early ’70s established Crumb’s reputation, the quality and consistency of the cartoonist’s work demonstrably improved in the middle of the decade, when he divorced Dana, slowed his frenetic pace, and stopped his LSD and pot use. (In a letter to Marty Pahls, Crumb wrote: “I think I was in a dope-stupor a lot of the time in the last seven years of so … Now I have this funny feeling that I’m gradually reclaiming my mind of something.”) In a sad irony, the underground era was nearing its end – done in by market oversaturation and obscenity busts (with Crumb’s incest-is-best provocation “Joe Blow” in Zap No. 4 creating particular upset) – but it saved the best for last: The seven issues of the 1975-76 anthology Arcade (edited by Spiegelman and Bill Griffith) served as a smartly curated showcase for the best of the underground artists, and Crumb’s contributions displayed a new level of artistic maturity. Other vistas also opened: Crumb had already found one artistic partner in Aline – they began jamming in 1972 on Dirty Laundry Comics and continued creating work together until her death in 2022 – and he added another fruitful collaborator when he began contributing to writer Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor in 1976.

In the subsequent decades, Crumb continued to produce increasingly diverse and fascinating work, including illustrations for Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang and two short books by Charles Bukowski (Bring Me Your Love and There’s No Business); logo, covers, illos, and strips for the Winds of Change newspaper (published near the Crumbs’ Winters, Calif., home); comics and illustrations for David Zane Mairowitz’s Introducing Kafka (aka Kafka for Beginners, R. Crumb’s Kafka); and covers for The New Yorker. More significantly, Crumb founded and edited his own anthology, Weirdo, in 1981, and although his quirky tastes ensured that individual issues were often highly variable in quality, the artist’s own contributions were among his best. Others – first Peter (Hate) Bagge and then Kominsky – eventually assumed Weirdo's editorial reins, but Crumb was featured in all 28 issues of the magazine. Excellent new solo comics also appeared (Hup and Mystic Funnies) and two publications that focused on illustrations: Id (explicit material from his sketchbooks) and Art & Beauty (primarily exquisite portraits of women who personify Crumb’s Platonic ideal of big butts and sturdy legs). With Kominsky, he produced two issues of Self-Loathing Comics, and the couple’s collaborations popped up in a surprising array of magazines. The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb – published way back in 2009 – represents the most recent of his solo cartooning work, but Nadel’s book promisingly reports that the 81-year-old artist remains active and has started on his first new comic book in more than two decades.

Nadel deftly covers all of this and much, much more – e.g., Crumb’s reluctant and often unhappy involvement in film (Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat, Zwigoff’s Crumb), the family’s exit to France in 1991, his ascension to museum and high-end-gallery respectability, his recent (and dismaying) conspiratorial tendencies – and he weaves astute critical insights on specific works into the biographical tapestry. Per Crumb’s instructions, Nadel makes no excuses for the racism, misogyny, and sexual violence that figure in the artist’s most problematic comics, and although he forgoes judgment of Crumb’s often highly questionable personal behavior, he’s exhaustive in his reportage, laying out the facts and allowing readers to render their own verdicts.

Like its subject, Nadel’s Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life proves unblinkingly honest and utterly masterful.

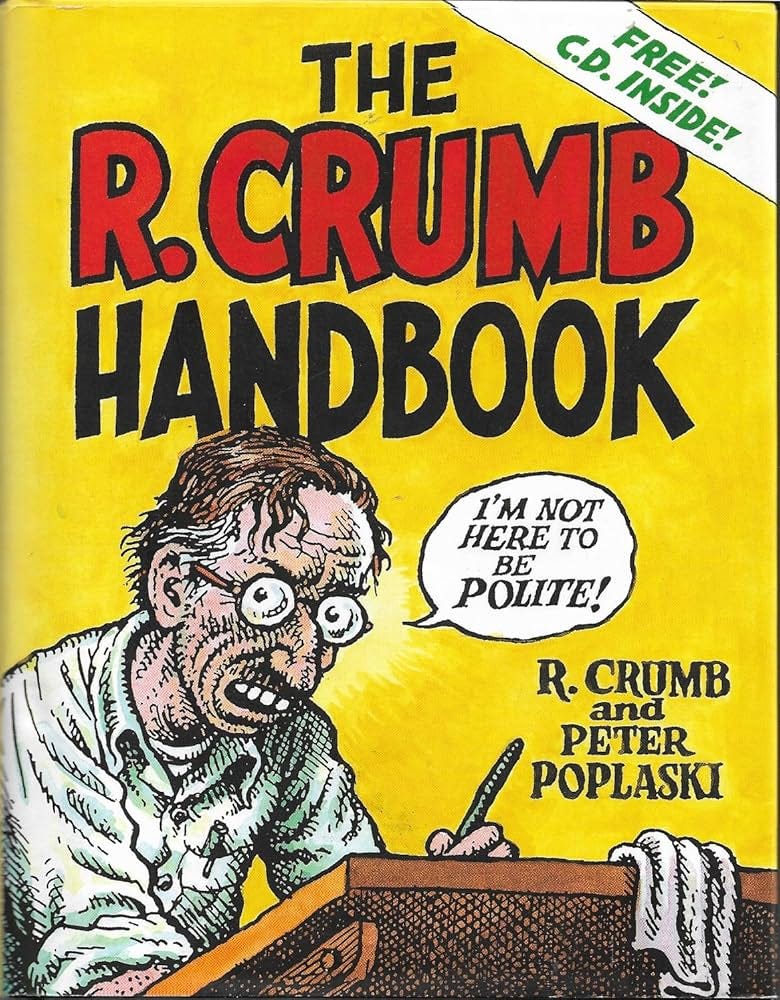

Below, I offer a trio of supplemental pieces: a survey of available Crumb books; my 1992 Riverfront Times review of Zwigoff’s Crumb; and my 2005 St. Louis Post-Dispatch review of the memoiristic R. Crumb Handbook. My next Re/Views post – which will conclude this run of comics-adjacent pieces – will offer some thoughts on two key Crumb collaborators, wife Aline Kominsky and friend Harvey Pekar.

Crumb Comix

The work of Robert Crumb – despite his cult celebrity and iconic status among underground-comix aficionados, pop-culture vultures, and counterculture survivors, hangers-on, and historians – is still known to most folks only in pirated versions (the endless ripoffs of his "Keep on Truckin'" art) or secondhand form (Ralph Bakshi's animated adaptation of his Fritz the Cat stories). If Nadel’s biography piques your interest, you’ll have several options to secure Crumb’s work, though the choices have narrowed in recent years. Virtually all of the artist's oeuvre was once available, but that’s no longer the case, unless you’re inclined to hunt for out-of-print titles and pay exorbitant prices.

At one time, for those dipping a tentative toe into Crumb's vast pool of work, the least costly approach would have been to sample a few of his solo comix. Unlike most mainstream comics publishers – who used to take a slash-and-burn approach to their books, treating them as non-renewable resources – underground publishers (e.g., Last Gasp, Rip Off, Kitchen Sink) kept many of their bestselling comix in print, going back to press when initial (and subsequent) runs sold out. Unfortunately, the purveyors of underground comix have now vastly reduced their publishing footprint, and with only a handful of exceptions (Last Gasp still offers some issues of Zap), those hunting for Crumb will primarily need to seek out book collections, not comix.

Fantagraphics Books made an attempt to reprint all (or at least most) of the artist’s work in book form with its 17-volume The Complete Crumb Comics. Nicely produced on high-quality slick paper with generous full-color sections, the Complete Crumb series featured a fair amount of ephemera – the first two volumes were juvenilia, for example – but for those taken with Crumb's artistic and satiric virtuosity, the books were invaluable compendiums. Although undeniably ambitious, the project concluded in 2005, having “only” reprinted work through 1992. Because Crumb defiantly continued to produce new comics (e.g., four issues of Hup, three issues of Mystic Funnies), the “complete” assertion of the title was long ago rendered invalid. (The claim wasn’t quite accurate regardless: An early book-length comic, The Yum Yum Book, was excluded from the series because the copyright was held by Crumb’s first wife.) Alas, these volumes are now regrettably out of print, though they can be found on used-book sites, generally for multiples of their original price.

Many other anthologies of Crumb’s work have similarly cycled in and out of print, including early examples such as R. Crumb’s Head Comix and R. Crumb’s Carload O’ Comics and later books such as The Life and Death of Fritz the Cat, The Weirdo Years by R. Crumb, 1981-’93, Crumb Family Comics, American Splendor Presents Bob and Harv’s Comics, The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book, and The R. Crumb Handbook, to name only a few. A number of these can still be found for (relatively) affordable prices through persistent Googling. Be forewarned, however, that if you’re psychologically inclined to completism, prepare for a long, expensive buying spree because Crumb’s compulsion to draw has produced a staggering, seemingly inexhaustible supply of material.

Quite likely, you’re more interested in sampling Crumb’s work than in running down every known scrap of his art. I’d recommend these as a starter kit:

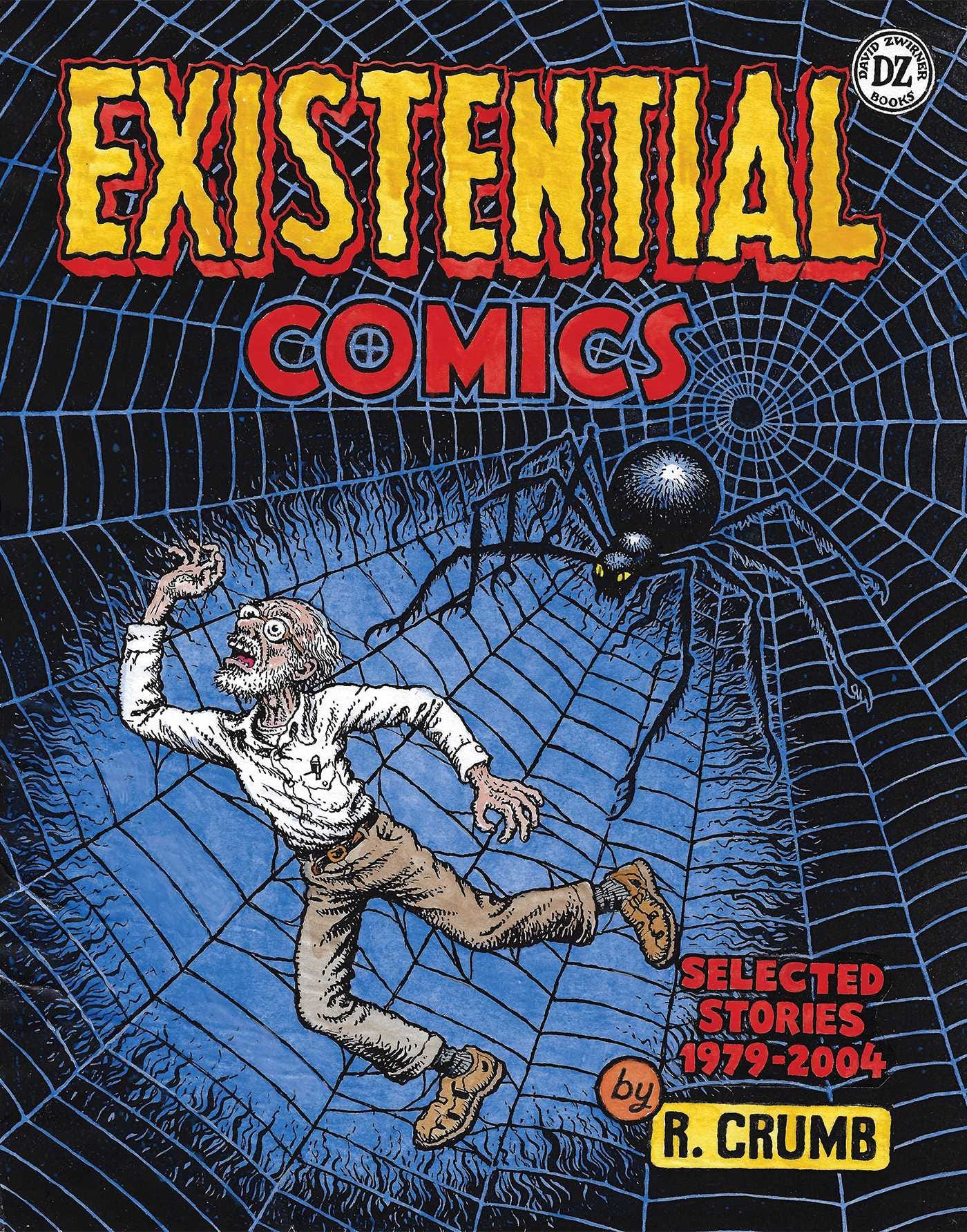

Nadel just edited a 25-story Crumb collection, Existential Comics, that serves as a companion to his biography, and it’s the best one-stop-shopping volume available.

If you want to acquaint yourself thoroughly with one of the artist’s most famous creations, try The Book of Mr. Natural: Profane Tales of That Old Mystic Madcap.

Drawn Together collects the many collaborations between Crumb and Aline Kominsky, including not just Dirty Laundry Comics and Self-Loathing Comics but also the pieces they contributed to such diverse publications as The New Yorker, Winds of Change, Weirdo, and Conde Nast Traveller.

Crumb’s most recent major work, The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb, is more impressive than immersive: Although the Bible’s first book ventures into quite strange and unsettling territory, which Crumb illustrates (sometimes amusingly) in his characteristically uncensored style, the artist remains surprisingly faithful to the text, making the book an odd capstone to his career.

If you want still more, other easily accessible possibilities include six volumes of Crumb’s sketchbooks from Taschen; books such as Crumb’s World, The Sweeter Side of R. Crumb, and R. Crumb’s Heroes of Blues, Jazz & Country (all of which emphasize illustration over comics); and novelties like R. Crumb’s Weirdo Card Set.

Nadel does a superb job of surveying Crumb’s life in his bio, but if you want more context for the artist’s early work and lasting impact, seek out Patrick Rosencranz’s Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution 1963-1975. And for a fathoms-deep dive into his Weirdo period, try The Book of Weirdo: A Retrospective of R. Crumb’s Legendary Humor Comics Anthology, edited by Jon B. Cooke.

Finally, for anyone who wants to hear directly from the artist, there are several options of note: the interview book R. Crumb: Conversations, edited by D.K. Holm; Your Vigor for Life Appalls Me, a revealing collection of Crumb letters; and The Comics Journal Library Vol. 9: Zap – The Interviews, which includes Gary Groth’s epic 1988 conversation with Crumb.

Crumb (1994)

Hilarious yet often horrifying, profoundly moving but deliberately provocative, even enraging, Crumb elicits a vast range of responses. Like underground cartoonist Robert Crumb himself – the fecund creator of such counterculture icons as Mr. Natural and Fritz the Cat (to name only the most famous of his dozens of creations) – Terry Zwigoff’s brilliant documentary confounds expectations; refuses to prettify, sentimentalize, or excuse; confronts the most intimate subjects with embarrassing frankness; and diligently explores difficult questions while bravely avoiding comfortably pat answers.

Crumb, in both the film and his frequently autobiographical comics, is a geeky misanthrope with a kinky, insatiable sexual appetite, a terrifyingly unfettered id, and oddly retro cultural tastes (in grossly simplistic terms, old equals good, particularly from a musical perspective). None of that would be of consequence to anyone outside of Crumb’s immediate circle of acquaintances if he were not also an astonishing cartoonist – equally adept with brush and pen (his beautiful, elaborate crosshatching produces a lithographic effect) – and a savage, howlingly funny satirist. Because of his narrative and artistic gifts, Crumb presents his peculiar, extremely unpleasant worldview with disturbing force and vividness: His extraordinary abilities magnify his faults.

Crumb’s work is frequently misogynistic – he reduces women to sex objects in the most literal sense – and often arguably racist, but the most distressing aspect of the cartoons is how frequently we respond with shamefaced laughter despite our horror: Visceral reactions temporarily short-circuit intellectual objections, compelling us in the process to confront our own dark instincts. Crumb doesn’t shrink from these controversies, marshaling a number of feminist critics to challenge the cartoonist’s viewpoint, including fellow underground artist Trina Robbins and former Mother Jones editor Deirdre English. Although Crumb freely acknowledges his demons, he appears unwilling (or unable) to discuss them seriously; his usual tack is simply to admit his sins and titter defensively with laughter. Crumb squirms visibly when talking with journalist Peggy Orenstein about her reactions as an adolescent to his cartoons’ explicit sexuality, usually so demeaning to women, and he’s especially uncomfortable when confronted with his irresponsible personal behavior by former girlfriend Kathy Goodell in a riveting, highly revealing conversation.

Crumb, however, is not only a finely detailed portrait of the artist: The film widens its focus to include illuminating sketches of Robert’s fellow dysfunctional-family members. Charles and Max – Crumb’s older and younger brothers, respectively – are haunted figures who make Robert appear positively well adjusted. Charles, a depressive, heavily medicated recluse and virgin – at the time he was filmed, he hadn’t ventured from his mother’s house in years – is a spellbinding figure: brilliant, witty, charming, painfully self-aware. No less eccentric, Max lives in a San Francisco flophouse, sits for hours on a bed of nails, and cleans his system by swallowing and eventually passing a yards-long cloth; needless to say, he has his own set of outré sexual predilections. Both brothers share Robert’s artistic talents. (Robert’s two sisters, regrettably, chose not to participate in the film, denying us a balancing female perspective on the Crumb sibling dynamic.) The gothic aspects of the family no doubt frighten, but the film remains nonjudgmental: The Crumbs’ militaristic, bullying father and blinkered, pill-popping mother are hardly exemplars, but they produced an authentic American genius. If the Crumb parents had been more “normal,” would the children have grown up happier and more fulfilled? And if so, would their talents have flowered as fully? Crumb doesn’t posit any facile answers.

Love him or hate him, Crumb elicits strong, primal feelings, and Crumb does the same: It’s a great and wondrous movie fully equal to its subject. No one who encounters it will emerge untouched by real joy, by legitimate anger, and by a powerful and overwhelming sadness.

The R. Crumb Handbook (2005)

Robert Crumb's status as the world's greatest living cartoonist places him in the enviable position of having the vast majority of his work in print.1 The bookshelves of Crumb obsessives already sag under the weight of anthologies, sketchbooks, checklists, commentaries, and compendiums of interviews and letters. Three volumes of Waiting for Food even collect his drawings on restaurant placemats.

Given the immense amount of Crumb available, there's scant need for another retrospective of the artist, but The R. Crumb Handbook, compiled with Peter Poplaski, somehow proves irresistible. A quasi-biography, the book features Crumb reminiscing about key periods in his life, complemented by deftly chosen stories and illustrations. Crumb also muses amusingly on a variety of topics: the frequent charges of racism and misogyny prompted by his "hard satire"; the media attention that accompanied both Terry Zwigoff's Crumb documentary and his recent move from underground-comic pages to art-museum walls; the onset of old age and imminence of death; and, of course, the libidinal appeal of big-bottomed women.

Although thick as a brick, the book suffers from its smallish dimensions, with comic pages either reduced in size or reformatted. And given the autobiographical nature of Crumb's work, a more generous sampling of relevant comics would have further enhanced the prose sections. The best source for one-stop Crumb shopping thus remains Poplaski's previous book with the cartoonist, 1997's The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book, which employs a roomier design and provides a more comprehensive overview.

But The R. Crumb Handbook wonderfully captures the artist's complexity. As he does in his comics, which combine gorgeous linework and outrageous content, Crumb presents himself uncensored, in all his contradictory glory: a charming curmudgeon, a self-deprecating egoist, a shy womanizer, a nostalgic progressive. And as a bonus, the book includes a 20-song CD of the old-timey music the banjo-strumming Crumb has recorded over the years with bands such as the Cheap Suit Serenaders.

This is no longer the case, as I note elsewhere.